This article is part of a series on How Historic Laurel Hill Cemetery Is Reinventing Itself. It is based on an interview with Ross Mitchell, Executive Director of Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia, PA.

Stoneangels: You mentioned admission tickets–the cemetery charged admission?

Ross Mitchell: Actually it was just the opposite. Laurel Hill was founded in 1836 (before railroads). Because of the Panic of 1837, this big economic downturn, things didn’t start well. It really took another couple of years to get the operation going. They re-interred some notable people here like Charles Thompson, Secretary of the Continental Congress [1774 to 1781], Hugh Mercer [Revolutionary War hero], David Rittenhouse [astronomer and instrument maker]. They wanted to bring some people who gave it a little more oomph.Before Laurel Hill, everyone was buried in their church burial yard and if you were not affiliated with a church-which almost everyone was-then you were buried in a Potter’s Field. And with the rapid expansion of the city all through the 1800s-the population was doubling roughly every 20 years – the churches would sell their property because of it’s increased value. Laurel Hill was intended to be a place far enough outside the city and non-denominational, where you would have family lots in perpetuity.

Stoneangels: Non-denominational…

Ross Mitchell: Right. It was very much intended as that. That’s why we have all these lots with coping around them, the dynasty lots with the stones being the same for the whole family. Laurel Hill began to have such cachet that it was almost too popular! In 1848, 30,000 people visited here within a 9-month period! They would come up on the steam ferry from Fairmount. I saw a sign on the pier in an old photograph that said “Ferry Rides to Laurel Hill.”

Stoneangels: What pier?

Ross Mitchell: Down at the Fairmount Water Works! There were ferry boats that would take people up to Laurel Hill. It was a popular destination. In the [early] 1800s, [Philadelphia] was not a pretty city. People were very afraid of disease, hygiene was not–

Stoneangels: Oh! The yellow fever business…!

Ross Mitchell: The yellow fever business, right. Death was a very common everyday thing. So people would leave the city in the summer and they would also come out to Laurel Hill for picnics–before there was Fairmount Park, before there was the Art Museum, there was Laurel Hill!

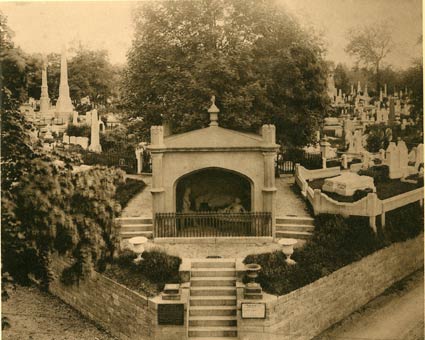

Vintage 1800s photo of main entrance to Laurel Hill Cemetery, showing its signature “Old Mortality” monument. Photo courtesy of Laurel Hill Cemetery.

They had public sculpture-“Old Mortality” [Laurel Hill’s signature gatehouse monument, designed in the 1830s by Scottish sculptor James Thom]-and it was landscaped, it was a park, a real garden cemetery. As a garden, John Jay Smith planted seven or eight hundred plants and shrub varieties that would thrive in this climate from all around the world. So it was very much intended to be a place that people wanted to come to, but so many people came that they had to limit how many people came! They started issuing lot holder passes.

Stoneangels: Do you think that’s because people were trashing the cemetery?

Ross Mitchell: No. It’s just that it was a little too crowded for the lot holders. It became too successful. One of my goals is to make it that successful again. My goal is to have another 30,000 people here in one year.

Stoneangels: I think the idea of having horse drawn carriage rides through here is phenomenal. You wouldn’t use old funerary carriages, would you?

Ross Mitchell: No I’m thinking more like the carriage rides like they have around Old City.

Next: Mourning Rituals: How Urban Youth Cope With Death and Grief